Interview by Glyn F. Edwards

Welcome to a new interview in our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman, a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms, and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human; it relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week’s interview features gay/queer Australian poet Stuart Barnes, author of Like to the Lark (Upswell Publishing, 2023), winner of the 2023 Wesley Michel Wright Prize, and of Glasshouses (UQP, 2016), winner of the 2015 Arts Queensland Thomas Shapcott Prize, commended for the 2016 Anne Elder Award and shortlisted for the 2017 Mary Gilmore Award. With Willo Drummond, Stuart guest-edited the ‘Queering Ecopoet(h)ics’ issue of Plumwood Mountain: An Australian and International Journal of Ecopoetry and Ecopoetics. Stuart, Nigel Featherstone, Melinda Smith and CJ Bowerbird are Hell Herons, an Australian spoken-word/music collective whose first record is due in June 2024. @stuartabarnes (X/Instagram) @hellherons (Instagram) www.stuartabarnes.com

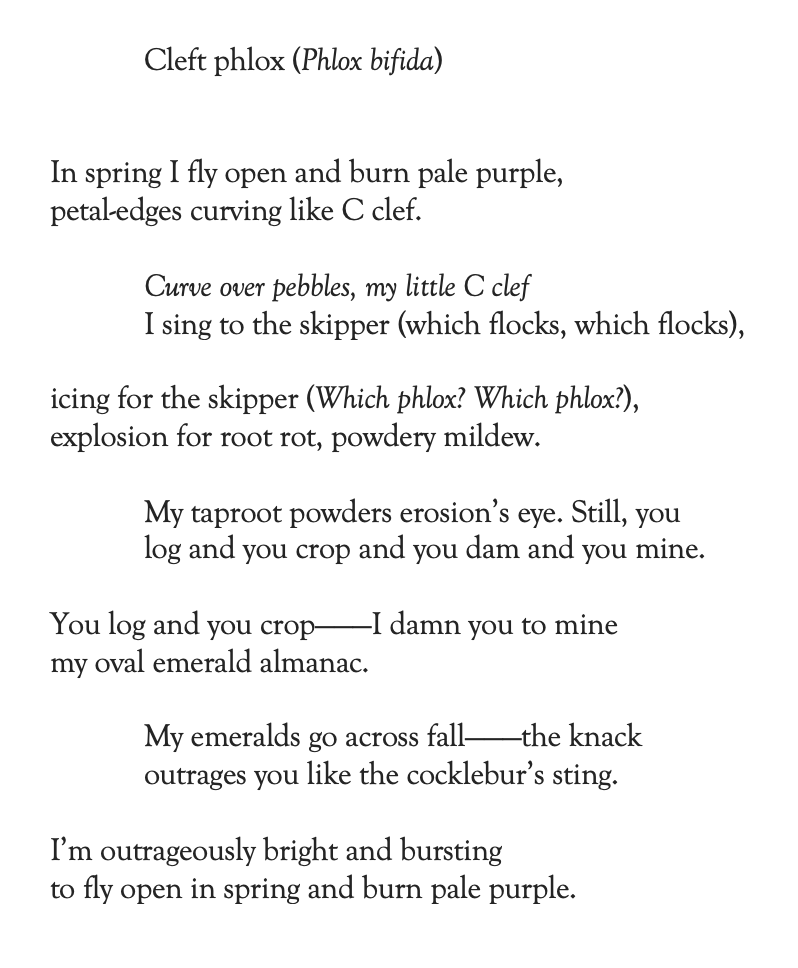

Duplex

You can find a Google Doc accessible version of this poem here.

Q1. Punctuation seems important to how you present your ideas on the page, particularly with regards to voice and polyphony. Can you elaborate on the poetics behind the italics, the parentheses, those dashes?

I’m infatuated with punctuation. When I was writing and editing my most recent poetry collection, Like to the Lark (Upswell Publishing, 2023), which includes a number of poems about plants (e.g., the walking iris) and animals (e.g., the 52-hertz whale) from their own points of view, I meditated on how best to present the voices of the more-than-human world. It felt inappropriate to do so in roman type and to imprison them in speech marks, so in ‘Duplex’ (Cleft phlox (Phlox bifida)) I italicised the song of the cleft phlox (to underscore the music’s elusiveness, I didn’t include a comma after ‘clef’) and the song of the skipper. The italics also signify the cleft phlox’s and the skipper’s incline to joy, high energy and vivid sexuality.

Traditionally, parentheses de-emphasise the text they enclose; in ‘Duplex’, they emphasise the text they enclose (‘(which flocks, which flocks)’, ‘(Which phlox? Which phlox?)’), accentuating the perfect rhyme and perfect and/or imperfect repetition that propel the poem. Additionally, the parentheses mirror the cleft phlox’s ‘petal-edges’ and its ‘bursting / to fly open in spring’, the tips of the skipper’s antennae and its motion and movement and the pebbles over which the skipper flies.

I adore the versatile em dash and have been experimenting with 3-em dashes (a nod to the long dashes of Sylvia Plath’s Ariel: The Restored Edition) in some of my third manuscript’s poems, of which this is one. The first 3-em dash of ‘Duplex’ (‘You log and you crop———’) symbolises felled trees, scarred stumps and ‘log[ged]’ earth prepared for ‘crop[ping]’ as well as the sudden termination of slow growth. The second 3-em dash (‘My emeralds go across fall———’) symbolises the passing of seasons (from summer, ‘across fall’, to winter); ‘fall’ corresponds with the aforementioned felled trees. Together, the 3-em dashes fragment the poem’s text, drawing attention to human beings’ fragmenting the more-than-human world and the cleft phlox’s obstinate evergreenness. Lastly, the 3-em dashes are tempo and expression markings for the text immediately preceding them: prestissimo agitato (as fast as possible, restless) for ‘You log and you crop———’; adagio sostenuto (slow and stately, sustained) for ‘My emeralds go across fall———’.

‘Duplex’ is a polyphonic composition, combining the voices of the cleft phlox (an explicit ‘I’), the skipper (an implied ‘I’) and erosion (an implied homophonic ‘I’). The I, here, is a plural pronoun—the poem’s cleft phlox speaks for every cleft phlox, the skipper for every skipper, erosion for all forms of erosion. The first five lines of the poem were inspired by the polyphonic refrain of Beach Boys’ ‘Good Vibrations’. Like this song, this duplex is a pocket symphony.

Q2. Critical responses to your poetry often discuss your experimentation with form. How did the duplex structure contribute to your decision making in ‘Cleft Phlox’?

I adore form and experimenting with form. Like Terrance Hayes, ‘I’m interested in challenging the law—within limits. I like bending more than breaking. If I break a poetic form completely, it’s anarchy—you may not know there was a form being challenged. I have to leave some residue of the thing that brought me to where I am.’ I love knowing that the duplex is, according to its inventor, Jericho Brown, ‘a ghazal that is also a sonnet that is also a blues poem’. The ghazal ‘invokes metaphysical questions’ (poets.org), the sonnet love, and the blues poem ‘resilience in the face of hardship’ (poets.org). The duplex was the perfect form for a poem concerned with, among other subjects, the Anthropocene, the cleft phlox and the skipper’s passion, and the cleft phlox’s ‘sheer toughness of spirit’ (the plant has an excellent resistance to root rot and powdery mildew, and tolerates drought and deer) (poets.org).

The duplex’s innate music was key to my decision making: the ghazal can be sung; the sonnet gets its name from Italian sonetto, ‘little song’ (poets.org); the blues poem ‘stems from the musical tradition of the blues’ (poets.org), which is characterised by the call-and-response pattern (in ‘Duplex’, the cleft phlox’s song is the call, the skipper’s song the response). I included more music: the cleft phlox’s ‘pale purple’ flowers correspond to violet, ‘from Latin viola’; the viola uses Alto clef, also known as C clef (which resembles the cleft phlox’s ‘petal-edges’); ‘little C clef’ is the cleft phlox’s affectionate name for the skipper.

I wanted to honour the sonnet’s volta, so the ninth line (‘You log and you crop———I damn you to mine’) subtly alters the language, tone and mood of the eighth (‘log and you crop and you dam and you mine’).

The duplex has three indented stanzas, or clefts—these reflect Phlox bifida’s deeply cleft petal lobes. The zigzags created by the poem’s clefts suggest movement: the cleft phlox’s growth; the rapid flight of the skipper (just one of the plant’s pollinators). Imperfect line repetition (with the poem’s last line echoing the first), perfect and/or imperfect radif rhyme and perfect and/or imperfect radif repetition suggest biological life cycles and permanence and/or impermanence.

Brown says the duplex, which I believe to be deeply alchemical, ‘is a form that is many forms’—so too the cleft phlox (a seed that is also a seedling that is also an established plant) and the skipper (an egg that is also a larva that is also a pupa that is also an imago). Thank god for his invention and his ‘Invention’, both of which continue to change the way I think about and write poetry.

Q3. In the UK, phlox is a diminutive but colorful alpine border plant. How is cleft phlox different in the USA, and what was your reasoning behind making it the speaker in the poem?

All species of phlox but one—the Siberian phlox (Phlox sibirica)—are native to North America. The native range of cleft phlox is E. Central USA: Arkansas (Vulnerable), Illinois (Secure), Indiana (Apparently Secure), Iowa (Imperilled), Kansas (No Status Rank), Kentucky (No Status Rank), Michigan (Presumed Extirpated), Missouri (Critically Imperilled), Tennessee (No Status Rank), Wisconsin (No Status Rank) (explorer.natureserve.org). Across these states, cleft phlox is a low-growing perennial that favours the dry, sandy and/or dry, rocky soils of wooded slopes, rock ledges, dry cliffs, bluffs, sandhills, dunes, cedar glades, savannas and prairies. The plant prefers full sun to partial shade and forms creeping mats of small, bright green leaves. The flowers are showy, slightly fragrant and lavender to blue to white, and appear from March to May, attracting skippers, butterflies and moths. Cleft phlox does well in cultivation and suits beds and borders, and rock, cottage and native plant gardens.

‘Duplex’ was sparked by my concerns over the plant’s USA conservation statuses and, as I see it, its inevitable extinction. The poem continues a tradition established in my second collection and emphasised in my third manuscript—writing about plants and animals from their own points of view. I consider their sense of agency. I’m interested in centring them and curious about what they might voice about their characters, their environments, the Anthropocene and so on. I believe—I hope!—that a shifting of perspective to the more-than-human from the human will evoke greater radical empathy from readers (I experience greater radical empathy writing as a plant than writing about a plant). I’m excited by the conversations between readers, poets and poems that might arise from this form of writing that I think of as a small act of provocation and a small act of preservation. Diverse approaches fascinate me—another poet writing about cleft phlox would create a very different poem.

Phlox is from Greek phlox, ‘“kind of plant with showy flowers”, literally “a flame,” related to phlegein “to burn” (from PIE root *bhel- (1) “to shine, flash, burn”)’ (etymonline.com). This brightness, energy and heat suggested the plant’s personality to me.

To Red Room Poetry Month 2023 I contributed ‘Sea Grape (A Decaying-Flourishing Sestina)’, about a botanic garden-bound plant from its own point of view, and this poetry prompt, which I sit with while writing about plants (it can be adjusted to writing about animals, fungi, etc.):

Meditate on your favourite plant. Research its botanical and cultural histories, its mythologies, its significance. Anthropomorphise it, ethically. What might it (not) need/(not) want to say, and in what form?

Q4. Sexuality and ecology are central themes in your poetic voice – do you consider them disparate or allied?

I’ve always felt very comfortable writing about ecology and the sexuality of the more-than-human world (some of the poems I wrote during childhood were about the love between rhododendrons and eucalyptuses, tiger quolls and Tasmanian devils, and the Derwent estuary’s freshwater and saltwater), but, until a few years ago, very uncomfortable writing about my (and other human beings’) sexuality.

Growing up among the kaleidoscopic foothills of kunanyi / Mount Wellington was astounding, but growing up gay/queer in lutruwita / Tasmania (the last Australian state to decriminalise sex between consenting adult men—the maximum penalty was 21 years in jail, the harshest in the Western world) was terrifying. The homophobia I experienced from five to 18 that manifested itself in psychological and physical violence contorted my perception of my sexuality—writing about it was torturous, then impossible. As a teenager I found solace in walking solo along the fern-edged trails near my home and with friends at beautiful Cradle Mountain–Lake St Clair National Park, Walls of Jerusalem National Park and Mount Field National Park (which, with other national parks and reserves, comprise the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area).

This walking with the environment, which continues 30 years later, and the earthing, sea swimming and beach meditation that I started in early adulthood, prompted me to write more frequently about ecology. This practice, and my deeper understanding of the diverse sexuality—of the extraordinary queerness—of the more-than-human world, enabled me to re-examine and start writing about my (and other human beings’) sexuality. These lines from Thích Nhất Hạnh’s The Miracle of Mindfulness still guide me and encourage me to walk daily:

I like to walk alone on country paths, […] putting each foot down on the earth in mindfulness[.] In such moments, existence is a miraculous and mysterious reality. People usually consider walking on water or in thin air a miracle. But I think the real miracle is not to walk on water or in thin air, but to walk on earth. Every day we are engaged in a miracle which we don’t even recognise: a blue sky, white clouds, green leaves.

I find working in traditional forms such as duplexes, sestinas and sonnets as well as forms I’ve invented (the terse-set, the flashbang, the decaying-flourishing sestina) revitalising; it evokes the freedom, joy and fearlessness I experience while walking. For me, traditional forms are capacious, generative frameworks within which to tend/transmute trauma and to explore the resilience of the more-than-human and the human worlds.

For decades I believed ecology and my sexuality to be disparate and disconnected. Now, I know they’re allied and entwined, and sense their corresponding with each other.

References

- Jericho Brown, ‘Invention’, poetryfoundation.org, March 18, 2019.

- Ralph Ellison, ‘Richard Wright’s Blues’, Shadow and Act (New York: Signet Books, 1966).

- Thích Nhất Hạnh, ‘The Miracle Is to Walk on Earth’, The Miracle is Mindfulness (Boston: Beacon Press, 1987).

- Terrance Hayes interviewed by Hilton Als, ‘The Art of Poetry No. 111’, The Paris Review, Issue 241, Fall 2022.

One thought on “More-than-human: A poem and Interview from Stuart Barnes”