Interview by Zoë Brigley

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week we meet Hilary Watson, a poet from South Wales. She was a Jerwood/Arvon mentee 2015 and graduated from the University of Warwick Writing Programme. She is an editor at thrutropian writing magazine Bending The Arc. She is working on her first collection and lives with her girlfriend and lurcher. (See: https://www.hilarywatson.co.uk/).

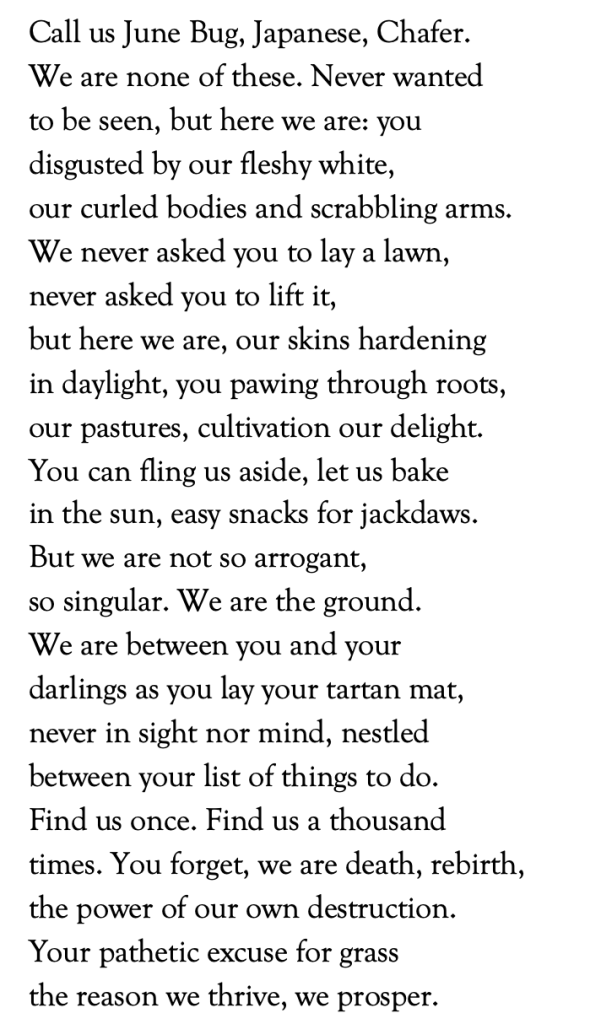

Chafer

Zoë Brigley: Just this past week, at the time of writing, I held a creative writing workshop at the university insectary. We were able to talk to experts keeping the insects for educational and research purposes about the creatures, and the students are going to write work inspired by the interactions there. One issue that came up is our tendency to seek to reduce the strangeness of the natural world by reducing creatures to human characteristics. This poem however suggest a different way of being for the chafer which is collective, and I would love to hear about how you found this address and voice for the poem.

Hilary Watson: Firstly, that writing workshop sounds fantastic. You and I have both studied under David Morley at the University of Warwick, and this seems right up his street. He was always marshalling us off to various scientific departments or art spaces or woodlands to push our poetry out of the classroom.

I distinctly remember Katrina Naomi talking about insects prior to me writing this. How a poet should be able to hone in on a particular patch of earth and find interest in it. At the same time, I was practically trying to find a solution to my lawn woes, as the small patch in my garden was prone to swampiness (not helped by the new addition of a dog!), so I was lifting the lawn in slices to remove the builders rubble, only to be quite repulsed by these grubbly little squirmers, that I firstly found skin crawling, and then was quite intrigued by my own disgust in them. After all, I’d ripped them out of the ground.

So, I entered into that challenge to human disgust (my initial, personal response), and challenged the notion of human singularity, and the false classification too – after all, Chafers, June Bugs and Japanese Beetle Grubs are not the same creature.

Zoë: I’m also thinking about fear of insects (‘our fleshy white’) and disgust. Insects are so radically different to us in their life cycles, their bodies, and the way they live in the world that humans often revile them. I must admit that years ago I was phobic about insects, but visiting the insectary helped me to understand that they think differently to us, have different instincts and motivations, and that helped me to come to terms with them. I wondered if the defiance in the voice here was created with some of this in mind?

Hilary: Yes, I think you’re right. I wouldn’t say I consciously have a phobia of insects, but then again, I can feel my skin crawling at the thought of lice or fleas or even the aphids I washed in their thousands off my lettuces this weekend. That’s why I was intrigued to lean in closer to the initial feelings of disgust when I saw these chafers pulled from the soil and left for the birds. No matter how many I picked out of the dying roots of the grass, there were more. That was the point. Insects make sense in relation to one another, in volume but also in transformative terms – a chafer, after all, is on its way to becoming a beetle – and even the way we interact with them as humans directly reflects this. We often talk about insects in the plural – it made sense to me to abandon the personal ‘I’ for ‘We’.

Zoë: I am a great lover of attention to line breaks, and the enjambment here certainly adds to the surprise and tension, as we read across to breaks to hear what the voice will conjure up next. Could you talk about the art of the line break?

Hilary: I had the good fortune to be mentored by Caroline Bird, as a Jerwood/Arvon mentee about a decade ago. I remember her teachings about the power of a line break – in many ways you get two bites of the cherry – the initial line and then the realignment once you read on. I think you see this in ‘Never wanted/ to be seen’. I get to stress the undesirability for the human in ‘never wanted’ and follow it by pulling the blanket of cover back over the chafer ‘never wanted to be seen.’ Even the end of that line aligns the disgust the human holds for the collective insects back in on itself towards herself through the lingering second-person pronoun ‘but here we are: you’. Line break, enjambment, end words, there are a lot of games we can play in our poems, which makes editing, how it looks on the page, particularly fun.

Zoë: Is there anything else you want to tell us about this poem?

Hilary: I’m still quite intrigued by how arresting I find the voice in this poem. It’s a direct assault on human superiority over creatures like grubs, bugs and creepy crawlies. I recently heard a politician mocking a scientific study that counts moths, as an absurd waste of money, which I found both frustrating and baffling. Insects, in all their vast variety and volume, are a quintessential part of the web of life on the planet. We could all do with getting a little closer and settling further into that discomfort of proximity (myself included).

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.