![www.gutenberg.org. (n.d.). The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Complete Herbal, by Nicholas Culpeper, M.D. [online] Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49513/49513-h/49513-h.htm.](https://modronmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/picture1.png?w=756)

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week we meet retired English teacher, Julie Runacres, who says she is “surprised to wake each morning to find I’m in the East Midlands again, my life ambitions terminated by two whippet puppies”. Her consolations include forthcoming and recent poems in Poetry Birmingham and 14 Magazine, and being shortlisted in the Wales Poetry Award 2023.

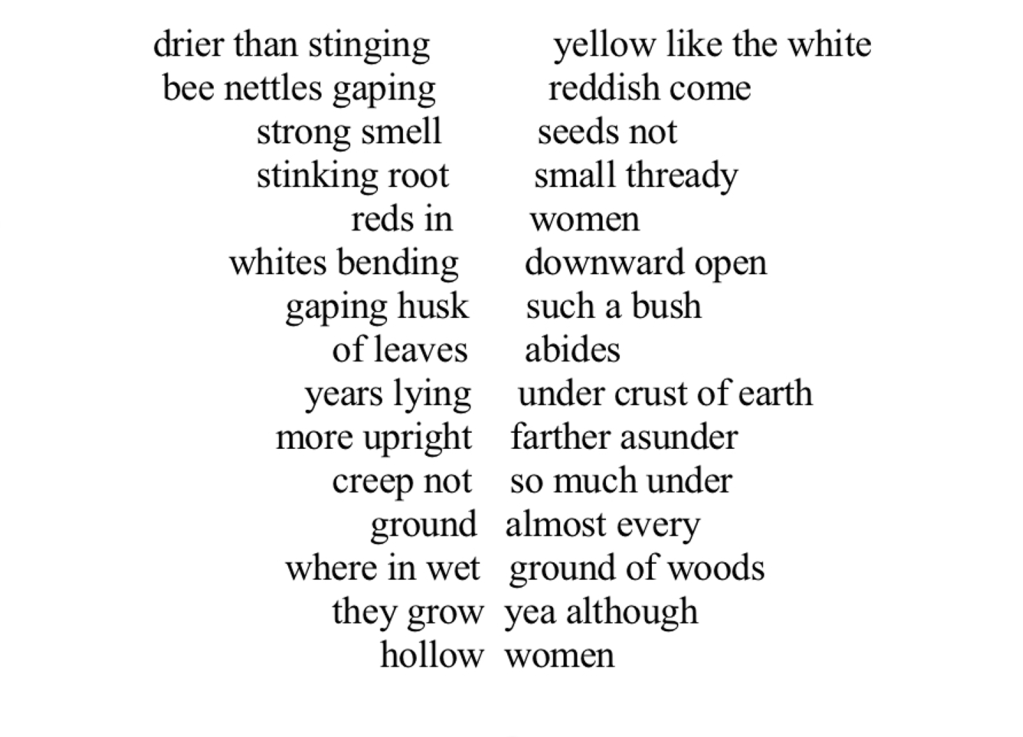

Archangel

Zoë Brigley: One of our interests on the team here at MODRON is herbalism, and so we were intrigued to find this poem talking about the traditions of women in use of plants. The herb of Venus reminds me of the scene in the 2019 movie, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (Portrait of a Lady on Fire), where the women concoct a remedy to abort the pregnancy of Sophie, the housemaid. I wonder what inspired this poem’s herbalism.

Julie Runacres: I’ve always been interested in the healing powers of plants. When I was a teenager, I volunteered at a play-scheme with a young medical student, who was going to qualify as a doctor and then set up as a herbal practitioner. I found her certainty completely disarming. I was studying for A-levels in sciences and English lit., and I came close to applying for medicine purely on the strength of her evangelical approach to healthcare and what we now call wellness. Needless to say, that would not have been a good reason for becoming a medic! Later, I loved poking about in the Culpeper herb shops that used to exist on the high street. I loved the big glass jars, the enticing arcane names and all the handwritten notes that accompanied them. Finding Nicholas Culpeper’s Complete Herbal as a Gutenberg text online was a joyful discovery. I was writing a lot of found texts at the time, mining contemporary news sources and juxtaposing them with phrases from marketing materials to create hybrid prose poems. It felt refreshing to work with a single text that is historic and transactional and rewarding to discover its poetics.

Zoë: The form of the poem might be an angel or a vulva. What is the attraction of concrete forms for you?

Julie: I think concrete forms can be overlooked because they’re assumed to be the domain of children’s poetry, gimmicky, or otherwise not serious. Yet reading George Herbert’s ‘Easter Wings’ or Guillaume Apollinaire’s ‘il pleut’ I see how, at their best, concrete poems enact and enrich their own meanings. The white space becomes as integral to what’s being communicated as the words themselves. In ‘Archangels’, the format of the text nods towards both angel wings and female genitalia, though the tapering white space in the middle also evokes a tap root. I didn’t set out to write a concrete poem from the outset; I was playing with phrases from the Archangel entry in Culpeper’s Herbal, and used them contrapuntally, so the poem reads as two columns or across the page. It all evolved from there. In the final draft, I was keen to make the final phrase ‘hollow women’ read as a single typographical unit, even while the sequential column reading gives separate phrases (‘they grow/hollow’; ‘yea although/women’). ‘Hollow women’ can be so many things, and, as someone who’s studied, read and taught T S Eliot for many years, I found the inversion of his ‘The Hollow Men’ quite satisfying!

Zoë: I am often intrigued by women’s environmental writing, as well as comparisons of violence against women and exploitation of nature. I am not sure you go quite as far as that in this poem, but there is a sense of overlap in the women and plants. The body and sap of the plant seems suggestive of the supposed messiness of women’s bodies sometimes maligned. Was that intentional or did it just happen in the writing of it?

Julie Runacres: I I think it was a bit of a chicken and egg situation, really. I can no longer separate the two. I was attracted to the Archangel entry in the first place by the bodily associations of the language, and these started to strike me as both predominantly female and weighted with judgment. There’s a sense of distaste that borders on disgust in the participle verbs and adjectives – stinking, stinging, gaping (twice), bending, lying – and the colours evoke menstruation, decay and tainted-ness. I agree that the poem is not explicitly drawing a parallel between violence against women and exploitation of nature, but I certainly ‘wrote into’ the discovery that the source text was rich in words that in some contexts are used to denigrate and dehumanise women. My aim was to bring these to the foreground, while at the same time drawing out the sensory qualities of the sounds. There’s so much going on with all the long vowel sounds, so much variation on ‘under’. I also had a lot of fun tinkering with the line breaks to create a poem that reads in two ways – across and down – and even enjambed mid-word, as in under/ground. The idea of the female and the earth is so rooted in myth and tradition that I was conscious of shaping something much more fragmented than I would normally, in the knowledge that it was likely to cohere as part of a collective memory.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.