Interview by Glyn F. Edwards

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week we meet Ilmar Lehtpere, an Estonian poet and translator. His translations of Kristiina Ehin’s work into English have won and been shortlisted for several awards. Wandering Towards Dawn is a selection of Sadie Murphy’s poetry and English versions of his own work. He has translated Welsh poet Laura Fisk’s poetry into Estonian.

Included here is a translated poem by Kersti Merilaas (1913-1986), a leading Estonian poet and translator who first made her mark in the mid-1930s during the first period of Estonian independence between the wars. She was expelled from the Writers’ Union of Soviet Estonia in 1950 and didn’t publish a book for adults again until 1962. Following the poem, Ilmar Lehtpere talks in interview about Merilass, translation, and the more than human.

Kersti Merilaas (tranlated by Ilmar Lehtpere)

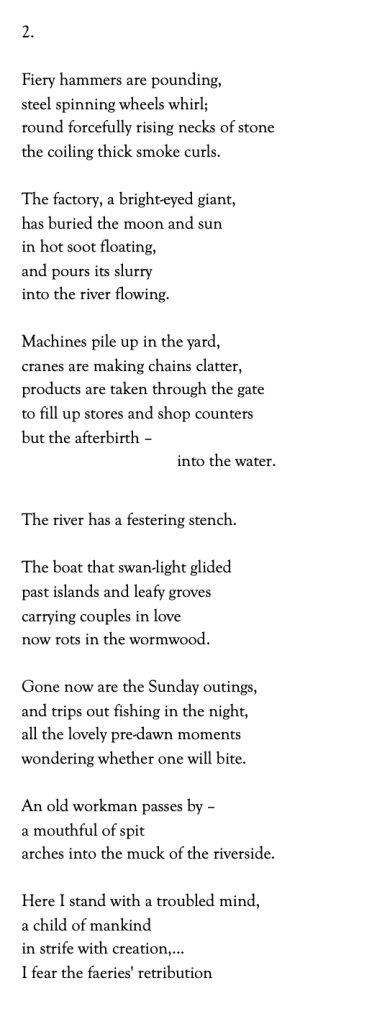

DEFILED RIVER

Glyn F. Edwards: Translation of poetry is such a daunting task that Rachel Bromwich, translator of Dafydd ap Gwilym’s mediaeval verse, described ‘the general belief that translation of poetry is untranslatable except at the cost of so great a loss as to call in questions the reasons for ever attempting it’. This is the first series of translations outside of Welsh to feature in Modron magazine, so the first questions will consider your fascinating process.

There is some contention about whether verse is the only acceptable medium for translating verse. Beyond rhyme, are there constructs in Estonian poetry, and indeed, in these Kersti Merilaas’ poems, that you wrestled to re-engineer in English?

Ilmar Lehtpere: At the heart of this question is the role of the literary translator. I recently went to a panel discussion about literary translation. All the the translators on the panel agreed that the translator should be present in the translation; that they should be free to interpret and modify the author’s text as they see fit, and to completely change elements of the original text that they didn’t approve of, including the meaning of the text, or portions of it. My heart sank. When I read a translation, I want to read something as close as possible to the author’s original work, not the translator’s. My aim, when I translate into English, is to find the author’s voice in English and to write the poem the author might have written if their English were good enough. I don’t wish to produce an English poem, but rather an Estonian poem that works in English, hopefully with a bit of an Estonian accent.

The only non-translator participating in that panel discussion suggested that the translator has a moral obligation to the author. I was surprised that that apparently hadn’t occurred to the translators – I had always thought it was fundamental. A writer’s international reputation rises or falls at least in part according to the quality of the translations of their work, and by quality I mean faithfulness to the original as well as the literary merit of the translation.

So I don’t do a lot of re-engineering. As a Finno-Ugric language, Estonian is structurally very different from English – fourteen cases, a lack of prepositions, very flexible word order, relatively few verb tenses, and only an ungendered third-person singular pronoun, to name a few of the more obvious differences. But I don’t recall structural matters ever being much of a problem while translating a poem. Reading bilingual books of poetry, I become suspicious if the original poem and the translation look wildly different on the page. That sort of translation may be a very good poem, but is it a true reflection of the original? Unless it has been done with the author’s consent and close collaboration, perhaps it should be called an adaptation rather than a translation, thereby acknowledging its distance from the original work.

Glyn: In as much as all art is a political act, Kersti Merilaas’ appears to have been prevalent in a period of particular socio-political upheaval. Do you believe these poems to principally be early forms of environmental writing, or do you consider the ‘Defiled River’ to operate as a wider analogy?

Ilmar: I’m not sure it is entirely useful to think in terms of those categories, as ‘Defiled River’ was written in a completely different social, political and historical context. Half of Estonia is covered in forest, real forest with wolves and bears. The forest, and nature in general, have always played a great role in the Estonian psyche – they have always been there, ever-present, integral. The Singing Revolution that led to the restoration of Estonian independence in 1991 started as an environmental movement. ‘Defiled River’ is another link in a long chain of environmental writing in Estonia reaching from folk tale and folk song through to the present day. It is different only in that it is responding to relatively new circumstances in 1965 – the harm done to the environment by industry. As such, it is obviously a courageous political act, protesting against the policies of the Soviet regime. The defilement can of course be viewed more broadly in metaphorical terms, but at the core of the poem is the essential reality and significance of the river.

Glyn: In some ways here you are translating not just a poem, but a different language and culture, a different time period, and you are also translating a female experience. If a translator is forced to reconcile a single meaning out of a choice of equally valid but never completely satisfactory alternatives, can you give some example of where syntax or metaphor forced you to ‘stand with a troubled mind’?

Ilmar: Yes, command of the language the translator is translating from isn’t enough; they have to be very familiar with the culture and history of the society the author comes from. And this of course includes female and male experience and points of view.

Words often don’t overlap perfectly between languages. Words in one language sometimes don’t even exist in another and need to be explained with a phrase. If a word has two meanings in the original text, that can also be explained. It requires thought, but an elegant solution that sounds like the author can usually be found. In the rare cases where I can’t find a solution, I just abandon the translation, or put it away for another time. I don’t look for equivalent English metaphors or images when I translate. As I said earlier, I’m quite happy for my translations to have an Estonian accent, as long as they work in English.

In ‘Defiled River’ only the last line – ‘I fear the faeries’ retribution’ – worried me a bit. English fairies are often those awful little winged creatures, and I was afraid that readers might not realise that Estonian fairies, or faeries, are akin to the powerful beings of Celtic folklore and mythology. But in the end I felt that was clear from the context, though I used the archaic spelling, just in case.

Glyn: As we search contemporary culture for new ways to narrate climate anxiety and biodiversity loss, to what degree do you feel translation offers a unique opportunity to consider the ‘river’s soul’?

Ilmar: Around twenty years ago an international survey found that Estonians are the least religious people in Europe, with only sixteen percent professing to be religious. Around the same time another study found that 65 per cent of Estonians believe that trees have a soul. Debates about tree-felling quotas are often front page news, as are local citizens’ initiatives against encroachments on the wild countryside. Poets take an active part in these debates.

Cultural diversity is vital to biodiversity. Every society, every culture has its own unique relationship with the natural world. Translation, particularly of poetry, can reveal those relationships to us, relationships we can all learn from. The ongoing Anglo-American linguistic and cultural colonisation of the world is an ever-increasing threat. The Poetry Parnassus festival which took place in London in 2012 brought together 204 poets, one from each of the countries participating in the Olympics. More than 75 of them wrote in English, dozens more in French, Spanish and Portuguese, though most of those countries have at least one or more indigenous languages of their own, languages as worthy of translation as any other, many of them no doubt endangered. When a language dies, the culture dies with it, along with a unique world view. I don’t wish to suggest for a moment that there is anything wrong with poets writing in English, or Spanish, or French if that is what comes more naturally to them. I just want to stress that indigenous languages need to be protected.

To counter this colonisation we have to, paradoxically, translate the work of the colonised into the colonisers’ languages to demonstrate their value to the rest of the world, and to preserve and disseminate what might otherwise be lost.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.