Interview by Glyn F. Edwards

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week we meet Eartha Davis, a woman of Ngāpuhi & Celtic heritage living on Wurundjeri land. She is the winner of the AAWP/Express Media Sudden Writing Prize and a 2025 Varuna Residency Fellow for her poetry collection màthair beinn. Her work is published or forthcoming in Wildness, the Australian Poetry Anthology, Cordite, Rabbit, South Coast Writer’s Centre Anthology, Flash Fiction Frontier, takahē, and more. She dreams of mountains.

Eartha Davis

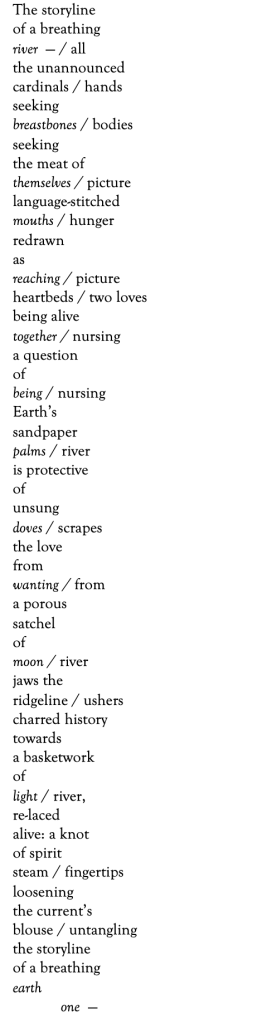

sgeulachd na h-aibhne

Glyn F. Edwards: Your title, ‘sgeulachd na h-aibhne’ translates to ‘story of a river’. Did you make an active choice to not use Gaelic in the body of the poem, and can you explain the reasoning behind not providing the direct translation of the title in the poem?

Eartha Davis: Very rarely do I weave Gaelic into the body of a poem. For me, Gaelic is a gateway, a vessel of entrance, a hand that ushers the reader forwards and ferries them towards breath. It is a language stippled with feeling; it is a language that cradles mystery of moments, the sacredness of listening, the spirit of Earth as it billows both within and outside us. Positioned before a sea of words, it invites the reader into stillness. It asks them to place a hand to their chest and soften their eyes. It asks them to feel into the tapestry of language and that which soars beyond its net.

Without a translation, readers must surrender direct avenues of knowing. They must surrender the script of instant knowing, of instant understanding, tuning instead to the music, the wildness, the river of wisdom nesting within every cridhe (heart), every cnàimh (bone). I am reminded of the words of Tsvetaeva: ‘the incalculability of the spirit.’

Gaelic is a language that not only nurtures the spirit and its incalculability, but is the spirit; ancestors, landscapes, birds, pulse-plushed hearts, the primal warmth of bodies, all nest within its filaments. Translation is not requisite for its sacredness to thrum; it does not sway the tide of spirit. In the words of John O’Donohue, ‘words become gossamer light…[fluttering against] the concealed terrain of the human heart.‘ I want the reader to experience this gossamer light, to plunge into its depths disburdened by direct knowing, by the glass of the literal, witnessing it bloom inside their human heart. Without a direct translation, the reader is called to feel.

Glyn: The ‘storyline of a breathing river’ moves in a sensual parallel to ‘the storyline of a breathing earth’. This is a poem of deep physicality, of ‘breasbones’, of ‘two loves being alive together’, of ‘fingertips unlacing the current’s blouse’. How do go about ‘untangling’ narratives in ‘sgeulachd na h-aibhne’, and is this familiar with how you consider the more-than-human in your wider writing?

Eartha: Our bodies are altars of Earth. They are one with the tides, the seasons, the birds that row across oceans and jewel the clavicles of mountains. And our human storylines – the dance of days, the huddling of hours, hearts – is one with the storyline of Earth. Earth and body breathe together. Earth and body are ‘two loves being alive together.’

When considering the more-than-human in my writing, I envision the human that unstitches her separateness from sky. I envision the human that cannot imagine what it is to walk without river, to sing without star, to live without listening and loving and learning. As I wrote in an early poem, ‘we are all Earth’s little darlings.’ We are her children. She is our mother.

My Māori ancestors have a whakataukī (‘saying’): ‘Ko au te whenua, ko te whenua, ko au’ (‘I am the land and the land is me’). We must nurse this whakataukī close to our chests. We must untangle the narratives – the storylines, the callous mesh, the ‘charred history’ – that tells us we are more-than-ocean, more-than-river, more-than-mountain. We are Earth. We are song.

Glyn: You incorporate two pieces of punctuation idiosyncratically in ‘sgeulachd na h-aibhne’. The em— dash appears to function as a exhalation point, or a voiced silence early on: ‘The storyline of a breathing river —,’ but there is a heightened intent in finishing the poem in the non-finite. Can you elaborate on your intentions in these two examples?

Eartha: The pulse of my writing is a return to body; a return to self, spirit, the soft, silty sacredness of presence. The em— dash is an act of reaching. It is the hand the heart extends in the heat of trauma, when the weight of here roars and ricochets towards there. It is the hand the Earth takes. It is the hand the Earth shelters through rain.

The em— dash is, by extension, the voice of body as it is ‘re-laced alive.’ It is the body asking river to usher return, remembering, to lap and lull and become the body’s hope, the body’s home. There is no complete union between ‘river’ and em— dash, between ‘earth one’ and em— dash; there is much journeying, much softening, to be done first. Slowly, through the tide of time, the em— dash shall inch closer; the spirit shall inch closer; and the storylines of human and river, of wounded one and water one, shall sail together towards a new dawn.

I am reminded of the words of Jane Hirshfield: ‘The body of a starving horse does not forget the size it was born to.‘ The human in sgeulachd na h-aibhne does not forget the size she was born to; does not forget that ‘hunger’ can be ‘redrawn,’ that ‘charred history’ can be salved by light’s ‘basketwork,’ that ‘a knot of spirit’ can be untangled by the very river that breathes before her.

Silence, when voiced, can soften into song. Silence, when voiced to river, can translate pain into prayer, bloat into blossom, loss into light. This salving by Earth is not a seamless process; the spirit cannot be re-threaded to body during a single dawn, a single dusk. It is a salving that must unfurl across a duration dawns, a duration of dusks. It is a slow, patient inching towards sun. sgeulachd na h-aibhne holds this recognition close.

Echoed in the sudden gap between ‘river’ and em—, ‘earth one’ and and em—, the whatumanawa (te reo Māor for ‘heartspace’) reweaves herself slowly; ‘the storyline of a breathing’ woman softens patiently beside ‘the storyline of a breathing earth.’

Glyn: Similarly, the oblique contributes to the visual aspect of the river, and also complements your syntax. Sometimes, it seems to offer you the freedom to explore alternatives, ‘palms / river’, ‘moon / river’, ‘light / river’, ‘steam, fingertips’, and sometimes it serves to singularly break the line, the current’s blouse / untangling the storyline’. Could you discuss more how this convention is employed in ‘sgeulachd na h-aibhne’, and whether it’s a feature prevalent in your work?

Eartha: For me, writing is an act of dancing. It is steeped in wildness. It is a song that sails across sentences and bursts with aliveness, presence, the sap of all things earthen, all things animal, all things river. I am guided by the words of philosopher and poet Nuar Alsadir:

We need nothing more than an overflow of flourishing corporeality, the sensation of being alive, embodied. There is no need to interpret, to hanker after meaning when faced with the out-shining of impersonal, unconscious, non-rational life-force energy, the flow of pure becoming, because you can feel.

The oblique is a fretwork of feeling. It is an outpour of the corporal, a rousing of the spontaneous, a waltz with wildness. It allows for the flow of pure becoming that Alsadir speaks of. sgeulachd na h-aibhne is not restrained by strict structural modes; it is not steered by a captain of classifiable form. Instead, it seeks to be river. It seeks to be fluid and untameable. It seeks to be the poetry that is listening, that is breathing, that is tracing the silk of here. Slashes are instances of breath. They are billowing wind-gusts.

When I think of slashes, I think of Yeats: ‘O body swayed to music, O brightening glance, how can we know the dancer from the dance?’ Poetry is the dancer. Slashes are the dance. The line is the stage upon which poetry’s choreography is rehearsed. And the oblique – the slant of syntax, the isolation of images, the wedding of others – is the music. My work seeks to make the music visible. I do not want to channel a glacial stillness; I do not want the reader to remain glued to the solemn, the silent, cemented in sentences. Instead, I want the reader to dance; I want the reader to swell with song, to feel the curtain of their heart rise, to see that poetry is the language of Earth.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.