Interview by Glyn F. Edwards

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

Originally from suburban Cheshire, in the north west of England, Sean Swallow (he/him) is a poet and garden maker with a lifelong connection with rural Wales. His poetry explores nature with a gay sensibility, and hopes to subvert traditional pastoral themes. Sometimes the speakers in his poems are outsiders, and they navigate themes of identity and belonging.

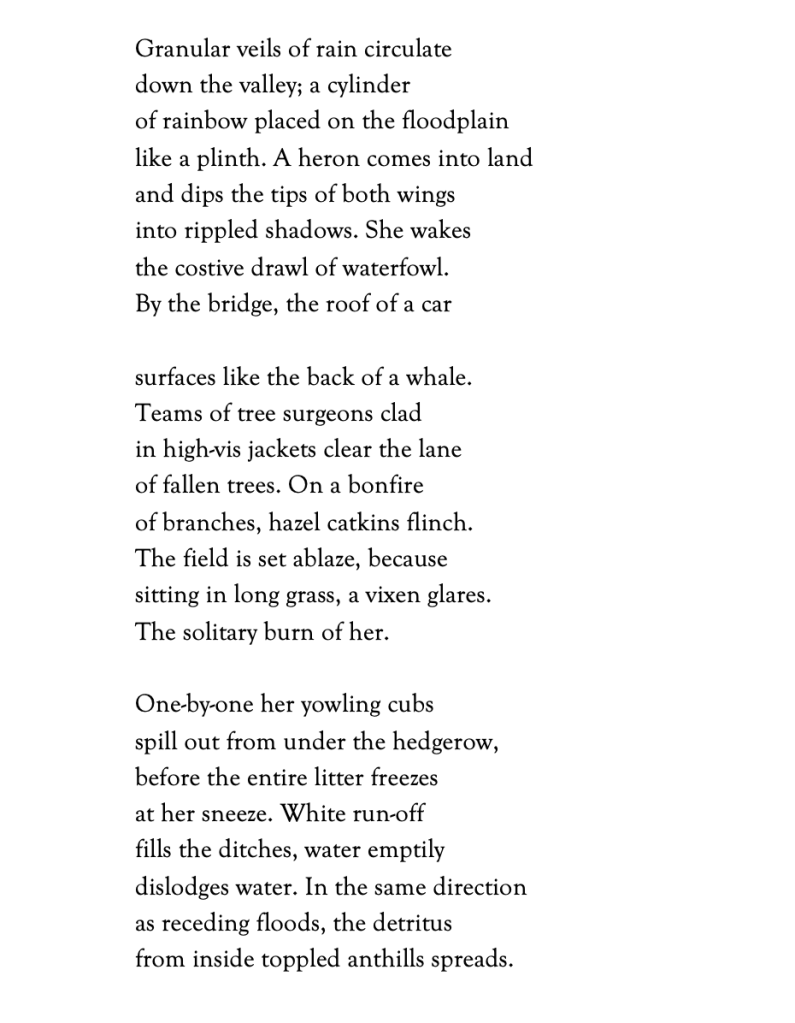

Before the Storm is Over

Glyn F. Edwards: This highly imagistic poem, the collocation of ‘bonfire’ being both ‘detritus’ and ‘vixen’ seems to operate as a symbolic and structural hinge. Can you elaborate on this particular turning points, and how you use pivots in your poetry more generally?

Sean Swallow: At first glance the speaker thinks the vixen is a flame which has leapt from the bonfire. She seems to ‘burn’ on the edge of a field. Her transfiguration is completed by the appearance of her ‘cubs’ and her ‘sneeze’ which signifies her maternal preoccupation. They represent the element of fire in a poem mostly about receding floodwater which, in the final stanza, topples the ‘anthills’ and exposes the ‘detritus’ within. These seed-rich contents might help regenerate the water meadow and, along with the cubs, they are suggestive of some kind of uneasy future.

I remember at some point in the writing of this poem I turned six quatrains into three octaves. The larger stanzas seemed to retain the steadiness of their smaller counterparts, yet gave more room for the water and ideas to flow. The resulting two spaces between the stanzas are further pivots which I handle in contrasting ways. Enjambment is meant to heighten the impact of the submerged car, whereas end-stopping the line about the vixen is meant to further impress her image upon the reader’s imagination.

Speaking more widely about my work, I think pivots are quite important. I hope they bring an element of surprise and help me to generate distinctive speakers. They also happen as I juxtapose different scales, periods of time, vocal tones and angles of perspective. Quite often, a deeper meaning is drawn out of an apparently throwaway observation.

I also ask myself what each poem is pivoting around. In this case, a specific moment in the life of the storm, as suggested by the slightly ominous title. And the central player is the river, which manifests different physical states as it withdraws and reveals a variety of consequences.

Glyn: As ‘water emptily / dislodges water’, with the flood comes the poem. Was there something significant about this particular weather event that led you to document it? Did the poem occur during or after the flood?

Sean: I remember it was Storm Brendan in January 2020. After the rain eased off I walked from The Forest of Dean to Cadora Woods above the River Wye. The water level was beginning to drop but Bigsweir Bridge was still closed. I made several notes which later provided most of the material for the poem, but I didn’t write the first draft until two years later. I had seen the truncated rainbow and the vixen with her cubs a month or so before. The submerged cars were contemporaneous, but they were upstream near Ross-On-Wye.

Because the River Severn also flooded, the bridges in all directions had been closed. The Forest of Dean felt like an island. There were even reports of geysers nearby, as all around us water seemed to burst out of holes in the ground no one ever knew existed. At the same time, Australia was ravaged by the most extensive bush fires the continent had ever experienced. The global mirroring of catastrophic water and fire events forged the key dynamic between elements in this poem. I think the poem took a year or two to reach its current form.

Glyn: ’Circulate’, ‘cylinder’, ‘surface’ and all the sibilants that come from utilising present tense and plural tense make this a poem of liquid phonics. How else did you seek to bring ‘lyrical’ aspects to the flood?

Sean: Alliterative ‘p’s’ drip through the sibilants with words like, ’placed’, ‘floodplain’, ‘plinths’, ‘dips the tips’ and ‘rippled’. Another pattern rocks back ad forth, perhaps like a boat, between the consonants ‘c’ and ‘w’. The following words cross over from the first to the second stanza, ‘comes’, ‘wakes’ ,’costive’, ‘drawl’ ,’waterfowl’ ,’car’, ‘back’ ,’whale’ and ‘clad’.

I like to think my use of assonance is also a bit watery (sorry). ‘Granular veils of rain’, sweeps down with the soft sounds of precipitation, and ‘granular’ and ‘veil’ juxtapose small and large scales. The veil perhaps invites to be lifted, in a figurative sense. ’The costive drawl of waterfowl’, mimics the reluctant sound of the birds, and ‘costive drawl’ could also describe the overall rhythm of the poem. I wonder if some readers may find the internal rhymes a bit unsubtle. I guess I feel, ’dips the tips’, and ‘freeze ’and ‘sneezes’ are a sonic counterparts to the excess which (literally) characterises a flood.

I substitute the lyrical ‘I’ with a Gaia-like focus on the interrelations between human and non-human species. A series of disruptions starts with the speaker noticing the truncated ,’cylinder of rainbow’, and then all the creatures take turns to alert one another to danger: speaker, heron, waterfowl, tree surgeons, vixen, cubs and ants.

The poem is also circular. The water that falls as rain in the first line recedes as the river in the last. The title and ‘granular veils’ of rain open up macro and micro concerns. The final image of drowned anthills is both a result of, and a microcosm of climate change.

In some ways, the vitality of the habitat is proven by being placed in jeopardy. The inhabitants even appear resilient until the level of insects is reached. The celebration of such natural patterns increasingly feels like a commemoration. As the storm ends, the river returns to its natural course. Yet a cosy ending would not have felt right, and the final word ‘spreads’ suggests an outward movement and stops the circle from completely closing.

Glyn: This poem is as at once ‘heron’ and ‘hedgerow’ and ‘high-vis’, where the ‘tree surgeon’ is as present as the ‘vixen’. As someone who has worked in garden design, do you ever find your current studies in eco-poetics complement or are at odds with aspects of your prior profession?

Sean: The truth is that I never seem to leave garden making behind, which of course is a good thing because it is a lovely thing to do. The industry and I have changed so much over the years and partly as a result of ecopoetics. Much of what I’ve learnt about the principles of design will always stand true, such as form follows function and right plant for the right place. Yet these days clients are often keen to tread more lightly in their gardens, and some really get into making gardens with modest ambitions, minimum disruption and less waste.

Because of my work I always have a store of images from nature which is very convenient for an ecopoet. There are many beautiful moments in a garden which are uplifting. The role of ecopoetics is to disrupt some of the assumptions that lie behind garden making. Why do we romanticise this back-breaking work? What power structures do gardens reaffirm? Is the rhapsodic response a kind of mask or is it a celebration which provides us with hope? By being so laborious and sometimes expensive to produce, is the wild-seeming aesthetic a kind of con? I welcome all of these questions in my poems but, understandably I hope, they might hinder my creativity as a gardener.

The tree surgeons symbolise human culpability and are relegated by being described by their occupation and uniforms. This portrayal might serve the poem, but it bears little relation to the professional tree surgeons I work with, all of whom are mindful of woodlands as wildlife habitat. And this dichotomy between the real garden and the imagined garden is typical. The gardens in my poems are far from perfect and I don’t think I could write about them if they were.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.