Is there a difference? According to the mechanical oracle at ChatGPT, there is. A nature poem, comes the reply, is concerned with celebrating the beauty and harmony of nature, is lyrical and contemplative, and seeks to evoke emotion in the reader. An ecopoem on the other hand, is concerned to draw attention to the damage humans have done to the world. It is more political. It can be angry and seek to provoke and disturb its readers.

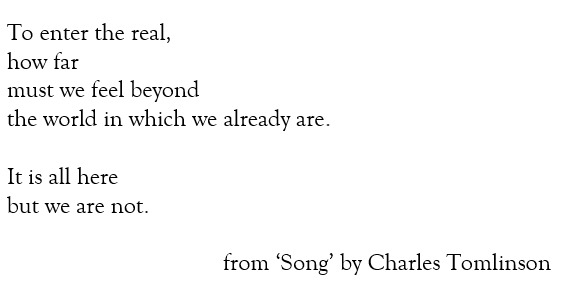

Sitting at the oracle’s feet I found myself feeling doubtful. Do poets write “nature poems” anymore? Is there any contemporary nature poem that does not have an awareness of the profound damage to ecosystems, of the frailty of our civilization, or of the looming consequences of Climate Change? Can a poem that takes nature as its subject ignore all that? If it does, surely it is not taking account of the whole, and so risks diminishing itself. Even if a nature poem doesn’t explicitly include such things, it is surely there in the readers response. A haiku might sketch a moment of fleeting beauty, the moonlight on the sea, for example. Can a reader respond to that beauty in a way that doesn’t eventually lead to contemplation of microplastics in the ocean food chain, and fleets of trawlers the size of factories ploughing the seabed to scoop up the last few fish that remain?

Probably not. And it’s a mistake to expect nuance of ChatGPT of course. But have we reached a point where the nature poem has so absorbed our contemporary awareness of ecology and the ecological crisis, that we can retire the term ecopoem? That would be nice, as it’s quite an ugly term, with a greenwashy feel to it. But I don’t think so.

Maybe it’s just me – and I’m not going to make any watertight arguments in a blog post – but I’m noticing a shift in the weather. If we’re all ecopoets now, then where is the ecological attention focusing next? What’s the next frontier for ecological awareness in poetry? Increasingly the poets I am drawn to are those who have absorbed the full implications our crisis and its origins in enlightenment materialism and have begun to move on. Where are they going?

Everything must change, we’re told, including our customary assumptions about what it means to be human, and what it means to be in relation with each other, and the wild world. We can no longer treat the world as crude, robotic, inert, an endless resource to be plundered. That way of thinking got us into this crisis.

So the future, if we have one, will of necessity be profoundly different, and all aspects of life will be harmonised to supporting and repairing fragile ecosystems, to being in “right relation*” as indigenous thinkers put it, with ourselves and with all the others, human and more-than-human, “respecting the sacredness of all life.”

Redrawing all the maps, the questions and problems and opportunities and excitements multiply. We’re on the brink of a new world. Maybe it’s the old world, the paradise of the palaeolithic, remembered and recognised belatedly, here and there, maybe too late, as the clock strikes midnight.

ChatGPT seems not to have noticed it. But for me, observing the development of this emerging awareness, however we label it, is one of the most exciting things about contemporary poetry.

*Right relation: an exploration of this idea can be found in Tyson Yunkaporta’s “Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World,” or Robin Wall Kimmerer’s “Braiding Sweetgrass.”

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.