Interview by Glyn Edwards

Welcome to our new series on writing #MoreThanHuman, a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms, and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human; it relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week’s writer is Joe Wilkins, the author of a novel, Fall Back Down When I Die, praised as “remarkable and unforgettable” in a starred review at Booklist and short-listed for the First Novel Award from the Center For Fiction. Joe is also the author of a memoir, The Mountain and the Fathers, and four collections of poetry, including When We Were Birds, winner of the Oregon Book Award, and, most recently, Thieve. Joe’s work has appeared in The Georgia Review, The Southern Review, The Missouri Review, Harvard Review, Poetry Northwest, The Sun, and Orion. He lives with his family in western Oregon.

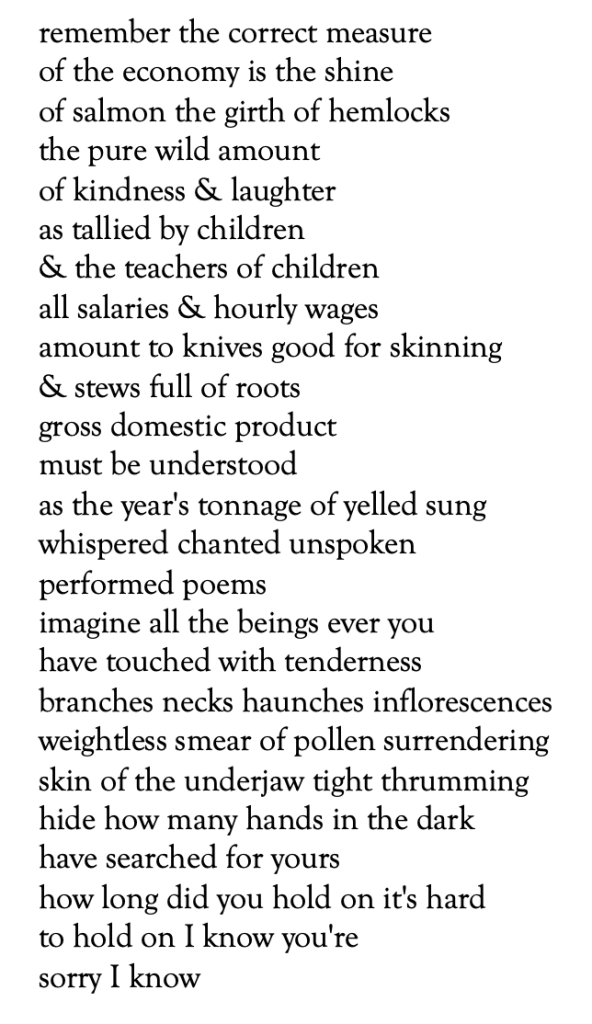

Dream Daughter Climbs a Boulder the Better for Us to Hear

You can find a Google Doc accessible version of this poem here.

The poem turns away from convention early on, but becomes particularly disorientating as it culminates. What poetic choices were behind the chaotic-despair generated by the voice of ‘Dream Daughter’?

There is great grief here, and that grief does indeed threaten to spin off into chaos—which is mirrored in the pile up of phrases and the radically enjambed lines—but I don’t read despair. At least not yet! Rather, by the end, as the lines shorten and soften, I hear the voice of Dream Daughter attempting to commiserate and to console, even as she implicates the addressee (that grief-riven other who is a stand in for all of us) in the undoing of good, hard, necessary natural systems.

Robin Wall Kimmerer contrasts the Potawatomi Nation’s culture with contemporary Western values to demonstrate concepts such as reciprocity and self-care. In the creation myth, Skywoman co-creates the Earth, does ‘dream daughter’ represent a more literal ancestor, or is she part of different, or new mythos?

I’ve read and admired Kimmerer’s work, and have had the chance to speak with her as well, and her wisdom and deep empathy have had a huge impact on me. My influences, though, are myriad, and Dream Daughter is a sort of epiphenomenon: I both know and don’t know where she comes from! Literally, she comes first from dreams. My wife and I have shared these dreams over the years of a daughter we don’t know far out in front of us, leading us.

The poem explores the societal and semantic meanings of ‘value’, considering ‘salmon’, ‘hemlocks’, ‘stews’, ‘laughter’ as measures of economic viability. While climate economics and post-growth consider the relationship between finite resources and profit, do you feel there’s a greater urgency for a ‘tenderness’ towards the more-than-human?

Oh, goodness—yes! That tenderness toward the more-than-human (not a naive sentimentality, but a true reckoning with the fact that we are all wrought up in natural processes, that by our very lives we do some damage and should seek to know and mitigate that damage, that we should strive for reciprocal relationships) is perhaps the moral issue of our time.

You’re based in Oregon, a state approximately the same size as the United Kingdom. While the Pacific Coast’s environmental concern and response is often narrated through a Californian prism, does ‘Dream Daughter’ address a private, municipal, national or international audience? And what must be done for more of ‘Us to Hear’?

I’m not absolutely positive about this, but I think the first time I encountered the Dream Daughter, we were living in Iowa, which is a long way from the Pacific! Yet that dream took place on a rocky, dramatic coastline much like the Pacific Coast of Oregon; Dream Daughter speaks from a specific place, always, but across dreams that place—coastline, riverside, bouldery mountain trail—has shifted, and I’ve tried to capture that in the poems. So I think (hope) the audience Dream Daughter is addressing is expansive. And if I only knew what could be done for us to hear! I think we keep speaking, we keep telling ourselves and others. And we do what is in our power to do in our homes and communities. And we engage our political systems in multiple ways and at all levels.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.