Interview by Glyn Edwards

Welcome to our new series on writing #MoreThanHuman, a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms, and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human; it relocates us in relation to the mystery. Today, we’ll look closely at a poem about the more-than-human and talk about the writing of it.

This week’s author is Elizabeth Gibson, a queer, neurodivergent poet from Wigan, living in Manchester. She is inspired by urban nature, and her solo show ‘The Reason for Geese’ was commissioned by Manchester Pride. Her work has appeared in Butcher’s Dog, Confingo, Fruit Journal, Lighthouse, Magma, The North, Popshot, Spelt, Strix and Under the Radar.

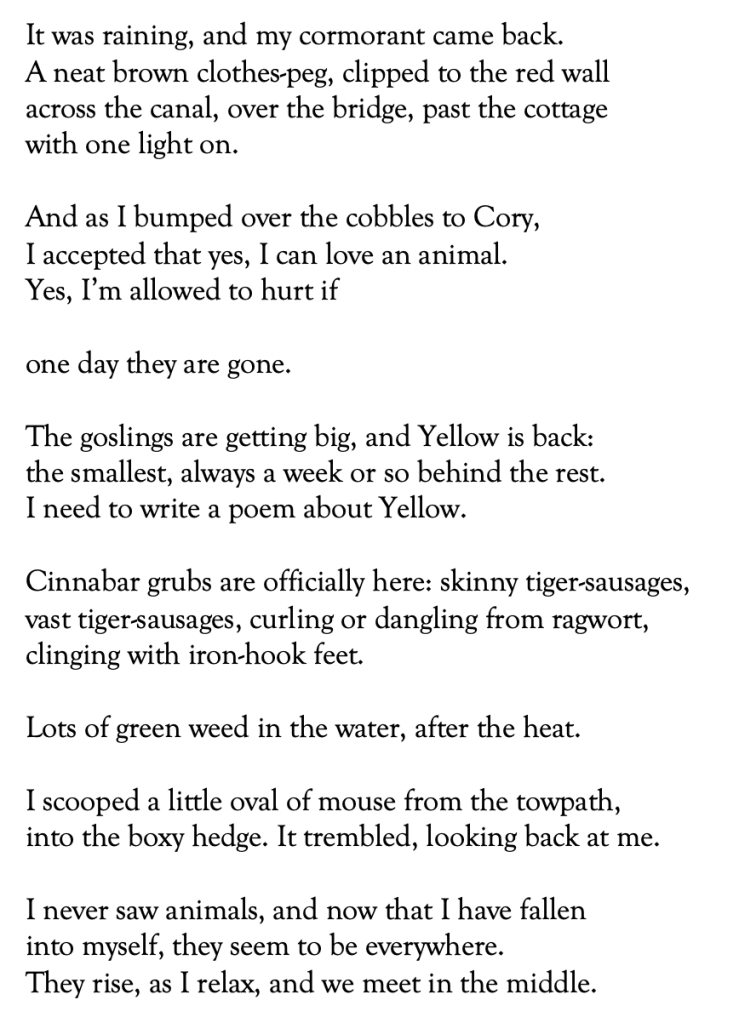

After the Heat

You can find a Google Doc accessible version of this poem here.

The poem takes the reader through rain, over the cobbles, and along the towpath. How much of ‘After the Heat’ was written in a single journal entry, or does the poem comprise multiple entries into one linear journey?

The poem is about one specific walk, but with moments linking back and forward in time to other walks along that route – what I love about my local walks is that time becomes looser, and I can connect to memories and build a relationship with a place across the seasons. The mention of Yellow always having been the smallest gosling gives the reader a glimpse into how I’ve followed the lives of the gosling family since they first arrived. The poem also implies an existing relationship with Cory the cormorant, who is a key figure in a number of my poems. (https://fruitjournal.co.uk/2023/04/14/elizabeth-gibson)

(continuing question) Is this a format typical of your writing?

A key way in which I write is to take down diary-style notes right after a walk, while it is all fresh, and then later on, I will work them into a poem. Often, patterns and themes emerge that I wouldn’t have been aware of until beginning the process of making a poem. Place, seasons, and cycles are really pivotal in my work.

In the same way the poem is about the cormorant, the cinnabar moths, the mouse, the speaker, it is also about goslings, therefore ‘I need to write a poem about Yellow’ is immediately self-fulfilling. To what degree do you feel a poem can investigate a single non-human-species?

I try and capture the essence of the creatures as I perceive it, and try not to seem like I’m trying to be an expert or tell readers how to view them – everyone will have a different response to an experience with nature. In my own journey, it is important to me to be humble and open-minded as to what I can learn from creatures. Often, natural links to aspects of my identity will come in, such as my queerness, neurodivergence, and having lived in different places and the constant hope to find a sense of belonging.

The title of the poem appears as subtly as the algae blooms. In its position though, ‘the heat’ also it feels directly related to revelatory lines at the end ‘I never saw animals, and now that I have fallen / into myself, they seem to be everywhere / They rise, as I relax’. Was there a catalyst to you being able to ‘meet in the middle’ with the more-than-human?

Two factors in the last couple of years have definitely influenced my relationship with nature. Firstly, I accepted and embraced my neurodivergence and the way that I experience life in a different way. Neurodivergence comes with struggles, but also the knowledge that I have something unique to offer in my writing. Secondly, in 2022, I underwent surgery for the first time, and in the lead-up and while healing, I spent a lot of time walking by the canals and in my local wild spaces. The animals I encountered – the goslings, Cory, and the caterpillars, as well as foxes, owls, and frogs – became familiar and comforting.

You are candid in your agency and vulnerability in your relationship with the natural world: ‘I can love an animal / Yes, I’m allowed to hurt if / one day they are gone.’ Is your writing motivated by a fascination with the more-than-human, or the growing anxiety in the wake of the Anthropocene?

Definitely a combination of these factors. The impact of humans on the environment and global warming are a constant source of anxiety and panic for me. However, I do also find moments of peace in nature, and a sense of connection to something bigger than me, a kind of spirituality. In terms of being vulnerable in my poems, I am leaning into that more now – I am turning 30 soon, and I feel that I’m in a place where I understand myself and feel comfortable sharing parts of myself in my work, in the hope that some readers might relate and feel understood and empowered.

Discover more from Modron Magazine

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.