Interview by Zoë Brigley

This is a special Earth Day 2025 edition of our series on environmental poetry. Today, we meet Jonaki Ray, author of Firefly Memories (Copper Coin, India) and Lessons in Bending (Sundress Publications, USA). Her poetry has appeared in POETRY, Poetry Wales, The Rumpus, Southword, The Margins: Asian American Writers’ Workshop, and elsewhere.

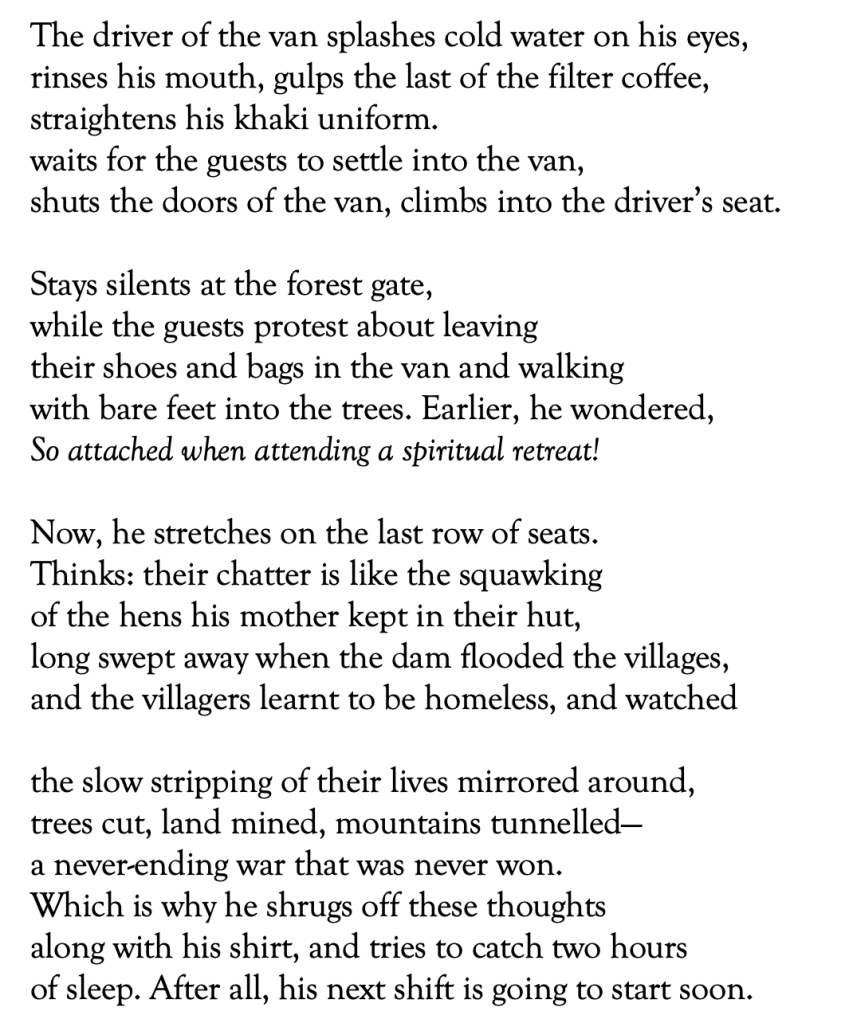

Night Shifts in the Jungle

Zoë Brigley: Enjoyed in the US and beyond is a recent hit TV series, The White Lotus, and there has been a great deal of discussion about its critique of ecotourism online. See this LA Times article for example which talks about how the show both satirizes ecotourism and profits from partnerships related to it. I wonder if your poem – with the driver’s perspective on the tourists who want the “spiritual retreat” but don’t want to be barefoot in the forest – has similar thinking points behind it?

Jonaki Ray: One of the thinking points I had when I was writing this piece was the rise in wellness and self-growth programs, including taking time off to ‘reconnect with nature’, but not many people analyzing about what is really changing on the ground. The essential lack of balance between development and degradation of nature is not addressed, and temporary breaks or holidays, or even trying to change things around us without truly understanding the bigger picture achieves very little. The other thinking point was that sustainability is a buzzword, but how many of us do anything about it. For the people who are fighting for basic survival, environment and climate change are words they don’t have the luxury to think about, yet the real cost of ‘development’ is borne by them. I think The White Lotus does bring out this aspect, and a part of its popularity is that it hits very close to what many of us would aspire to—enjoying a luxurious holiday, without really thinking of the machinery and exploitation that exists behind that lifestyle and that is needed to set it up and the cost to keep it going.

Zoë: I find the driver’s perspective intriguing, as he has lived through exploitation of the lands and the flooding of villages. His focus seems to be more about the practicalities of survival? Where did this character spring from for you?

Jonaki: This character is a summation of many people I have met during my travels. I often travel to places off the grid and try to understand the perspectives of those who manage or own these places as well as the staff who work behind the scene to maintain these. Also, at least in India, many of the daily tasks are carried out by almost an army of guards, nannies, cooks, drivers, and so on. Talking to these people, most of whom have come from villages far from the metropolises, made me realize that while we can sit in air-conditioned rooms and talk about the impact on the environment and climate change, real change will only happen if we come up with a way to provide livelihoods in a sustainable and environment-friendly way to people who have lost their land or homes, and are trying to survive through these jobs.

Zoë: David Lodge talks about poems as intense moments of experience pressed into lines and stanzas. Something I enjoy about this poem is that it gives us a vivid glimpse of a different point of view, almost a compressed short story, with a sense of warning. Are there particular writers or poets who have influenced you in the writing of this, especially with the expedient way that it creates a complex situation and story?

Jonaki: That’s an interesting question! I had actually thought of a story story initially, which described the life of a guide who is struggling with the stresses of his job, yet is glad to finally have a livelihood. I was influenced by many new items I read online, some pieces of ecopoetry I read from my favourite journals like Poetry Wales, Poetry and Aesthetica magazines. Additionally, I was inspired by the work of poets such as Robert Hass, and in the realm of Indian writers, the fiction of Aravind Adiga.

Stay up to date with Modron—subscribe for news, submission calls, and our regular series featuring environmental campaigns, writer interviews, thought-provoking essays, and reflections on our connection with nature.