Interview by Zoë Brigley

Welcome back to our series on writing the #MoreThanHuman. We offer a set of interviews with poets and writers on how they approach writing about the environment. The more-than-human is a phrase that seeks to side-step traditional nature-culture dualisms and draw attention to the unity of all life as a kind of shared commonwealth existing on a fragile planet. It also reminds us humans that there is more to life, that there is more world, than the human. It relocates us in relation to the mystery.

This week we meet, Chloe Hanks, a poet based in York. Recipient of the V Press Prize for Poetry in 2020, she has published 4 short poetry projects including May We All Be Artefacts (2021) and I Call Upon the Witches (2022). She is currently completing a PhD in Creative Writing and is Festival Director for York Literature Festival.

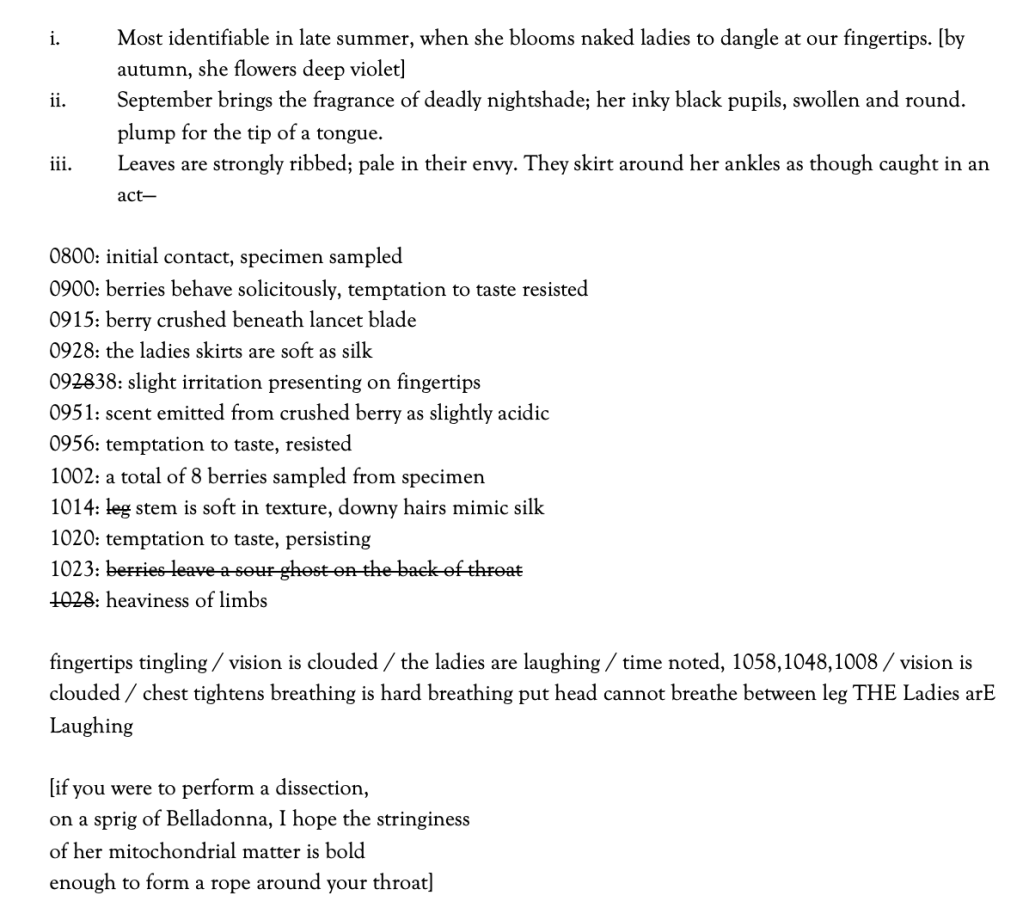

Fieldnotes | Sampling Belladonna

after Leah Atherton’s ‘Field Notes’

Zoë Brigley: Could you begin by telling me about the inspiration for this poem: Leah Atherton’s ‘Field Notes’?

Chloe Hanks: When writing the critical thesis to accompany my creative PhD submission (a poetry collection titled Such Violent Glamour), I was researching for a chapter on writing the human experience through personifying the non-human. Leah Atherton’s poetry pamphlet, Mycelium published with Fawn Press in 2024 was a huge inspiration both for my creative work and the critical thesis.

Atherton’s use of form is inspiring. Her ‘Field Notes’ poem(s) bookend the pamphlet, and the reader is somewhat invited to read these as sister poems or as one cohesive piece that is woven throughout the collection, behaving somewhat like Mycelium itself. I had been drafting poems from the perspective of poison plants and personifying them to create voice. Somewhat dissatisfied with my poetic impression of Belladonna, I adopted the form of a field note inspired by Atherton’s piece to breathe a new life into my poem. The final fragment of the poem, structured as an aside through use of box brackets, is taken from an earlier draft of a Belladonna poem and, for me, is the personified plant speaking back through the archive document.

Zoë: Something I enjoyed about this poem was the ways that it challenges the logic and supposed objectivity of the field note. These are not typical field notes, but the things it does record may be just as valid. Could you say something about this?

Chloe Hanks: I refer to my work, and creative work that plays with the archive and documentation in this way, as creative intervention. This poem begins in a very logical place, with the speaking voice presumably that of the ecologist making notes as they sample Belladonna. As the speaker is then poisoned after being tempted to taste the plant’s fruit, the sequence of notes become more illogical through supposed mistakes or errors as the speaker continues to scrawl. My favourite part of the poem is the end where the subject of the poem, the Belladonna plant, speaks back in box brackets. This section is defiant, with implications of a vengefulness. This is demonstrative of poisonous plants as a metaphor for vengeful women which is a device I have used throughout my collection, Such Violent Glamour, to construct female voices that are otherwise missing from the particular archive I was working from. To me, this poem is a very literal demonstration of what creative intervention into archival material achieves, a translation of what an archive cannot tell us.

Zoë: I felt that there was a crossover in this poem between plants and women. Often they are used as the opposite or foil of patriarchal civilization. Was that conscious or did it just emerge in the writing?

Chloe Hanks: This was certainly conscious. I mentioned the piece as part of a larger collection. In this collection, I consider the concept of women’s histories and what is missing from the archive. In particular, I am writing about a series of poisonings that date to 17th Century Italy. However, through interest in the work of Jill Burke and her hypothesis that much of the female experience is archived in the history of beautification because our experiences were treated as other, or an aside, in many other historical events or cases, but beautification remains our history. Naturally, I found the relationship between poison and beautification and unlocked a whole other thematic link to botany.

Critically, my work is concerned with the patriarchal consignation of the archive in a more general sense. Thus, the most fascinating conclusion I have drawn through my poetic work is that through personifying poisonous plants to construct female voices otherwise absented from the archive, I have discovered an empowering metaphor. The particular women I am writing about were guilty of poisoning their husbands to escape marriages. Poisonous plants are not harmful if left alone, and this is a very powerful metaphor when applied to the notion of so-called murderous or vengeful women.

Zoë: Is there anything else you want to tell us about this poem?

Chloe Hanks: This poem is a product of several discarded drafts, and I had almost given up on finding the right way to say these things. I hope that the piece, in the company of this interview, is demonstrative of how important reading is to our writerly practice. Going back to Atherton’s pamphlet and considering the mechanics of form were vital to bringing this piece to life. Writers borrow all the time. Give credit where it’s due and keep reading things.